HOW AN AUSTRALIAN DATA PRIVACY CASE SIGNALS STRICT LIMITS ON FACIAL RECOGNITION TECHNOLOGY USE IN THAILAND.

A landmark ruling against Australia’s hardware store “Bunnings” for the unlawful use of facial recognition technology (FRT) serves as a wake-up call for Thai businesses.

The November 2024 decision by Australia’s Privacy Commissioner – finding mass biometric collection without consent, transparency, or proportionality illegal – directly parallels Thailand’s Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) requirements. With Thai regulators increasingly scrutinizing FRT deployments (like recent controversies at 7-Eleven Thailand and MBK Center), companies should urgently align practices with PDPA mandates or face severe penalties.

The Bunnings Precedent & Its Thai Relevance

Australia’s OAIC ruled Bunnings violated privacy laws by scanning faces across 62 stores (2019–2021). Key findings included:

- Illegal Collection: Capturing biometrics without consent breached "sensitive information" protections.

- Inadequate Transparency: Small signage and vague policies failed to notify customers meaningfully.

- Disproportionality: Mass surveillance of all customers was unjustified for theft prevention.

- The "Milliseconds" Myth: Data held for 4.17 MS (Bunning’s quoted processing time to determine facial parameters) still constituted illegal "collection."

Thai Parallel: This mirrors PDPA’s core tenets. Biometric data is explicitly classified as "Sensitive Personal Data" Under Section 26, demanding explicit consent. Recent Thai media exposés similar FRT misuse:

- 7-Eleven Thailand: Faced public outcry in 2023 after deploying FRT without clear signage or consent mechanisms, violating PDPA’s transparency requirements (Bangkok Post, 15 March 2023).

- Bangkok Mall Pilot: A major shopping center halted FRT trials in 2024 following PDPA Office warnings about insufficient customer notice (The Nation, 2 May 2024).

PDPA vs. Bunnings: Legal Alignment

Thailand’s PDPA (fully enforced since 2022) and Australia’s Privacy Act share stringent FRT restrictions:

| Issue | Australia (Bunnings Ruling) | Thailand (PDPA) | Thai Media Context |

| Biometric Data Classification | "Sensitive Information" | Section 26: "Sensitive Personal Data" requires explicit consent | The PDPA Office repeatedly emphasizes the sensitivity of biometrics in its guidelines (2023). |

| Consent Requirements | Mandatory, "impracticality" rejected | Section 19: Explicit, informed, freely given consent required. No exceptions for convenience. | The 7-Eleven case shows that implied consent (via entry) is insufficient under PDPA. |

| Transparency Obligations | APP 5.1: Notice must be clear, accessible | Section 23: Must inform subjects of purpose, retention, and rights before collection. | MBK Center pilot criticized for "discreet signage," failing PDPA’s prominence standard (Prachatai, 30 April 2024). |

| Proportionality & Necessity | Mass surveillance deemed disproportionate | Section 24(3): Collection must be "necessary" and "least intrusive" means. | Thai retailers have been warned that FRT must be a last resort, after enhanced CCTV or guards (PDPA Office Guidance, 2023). |

| "Collection" Definition | Milliseconds-long processing is still illegal | Section 19: "Collection" includes any capture/processing, regardless of duration. | Thai tech firms warned that transient data processing still triggers PDPA compliance (Digital Economy Council, 2024). |

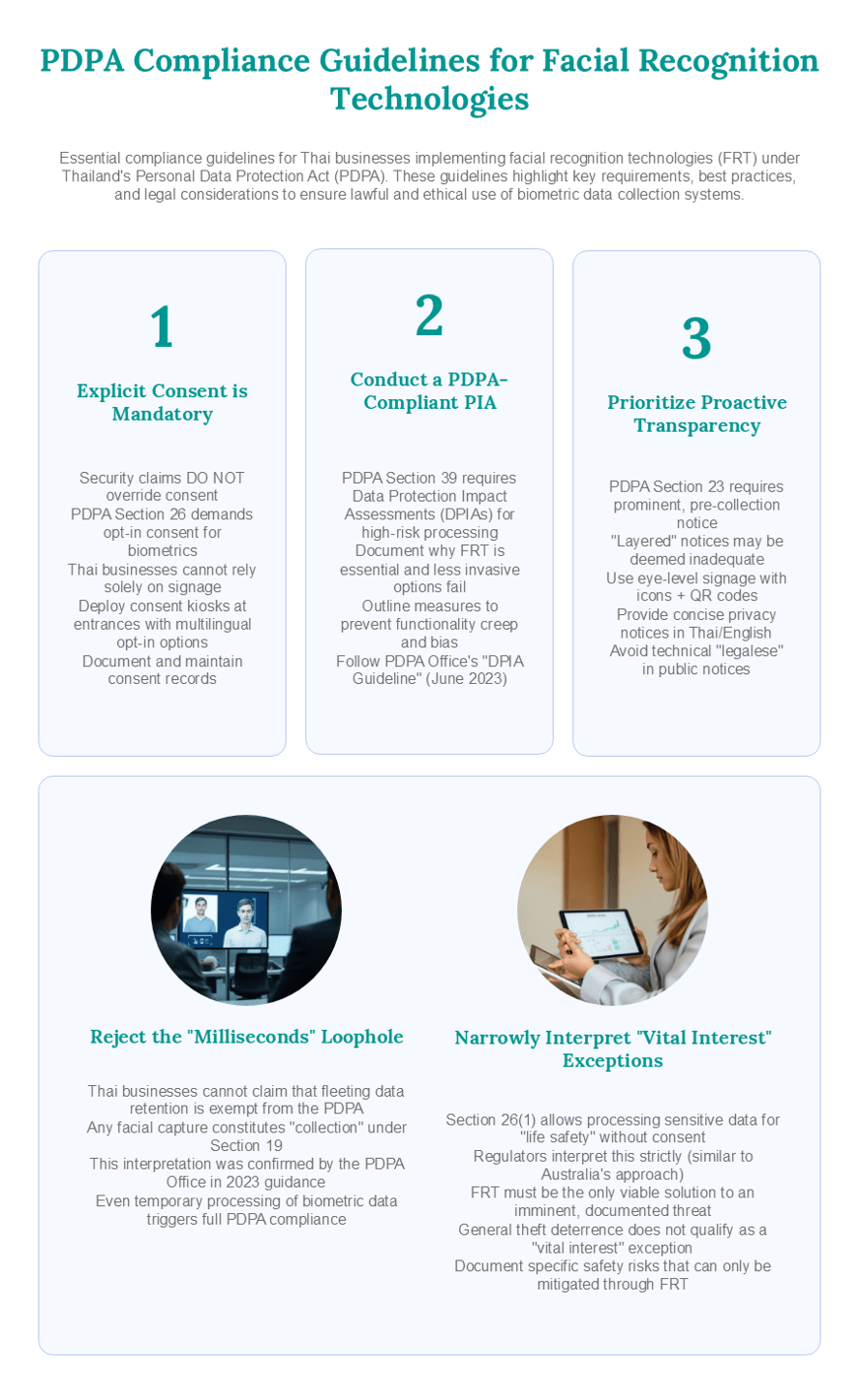

PDPA Compliance Guidelines for Thai Businesses

- Explicit Consent is Mandatory:

Security claims DO NOT override consent. PDPA Section 26 demands opt-in consent for biometrics. Bunnings’ "impractical consent" defense failed; Thai businesses (such as 7-Eleven) cannot rely solely on signage.

Best Practice: Deploy consent kiosks at entrances with multilingual opt-in options. Document consent records. - Conduct a PDPA-Compliant PIA:

Australia mandated PIAs for FRT. PDPA Section 39 requires Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) for high-risk processing (like FRT). Document:- Why FRT is essential and why less invasive options (e.g., traditional CCTV + guards) fail.

- Measures to prevent functionality creep and bias.

(See PDPA Office’s "DPIA Guideline," June 2023").

- Prioritize Proactive Transparency:

Bunnings’ "layered" notices were deemed inadequate. PDPA Section 23 requires a prominent, pre-collection notice.

Best Practice: Use eye-level signage with icons + QR codes linking to concise privacy notices (Thai/English). Avoid "legalese." - Reject the "Milliseconds" Loophole:

Thai businesses cannot claim that fleeting data retention is exempt from the PDPA. Any facial capture constitutes "collection" under Section 19 – as confirmed by the "DPIA Guideline," June 2023 guidance. - Narrowly Interpret "Vital Interest" Exceptions:

While Section 26(4) allows processing sensitive data for "life safety" without consent, regulators (like Australia’s) interpret this strictly. FRT must be the only viable solution to an imminent, documented threat – not general theft deterrence.

The Path Forward: FRT Under Thai Scrutiny

With FRT adoption rising in Thai retail, malls, and airports, regulators are escalating oversight:

- Suvarnabhumi Airport FRT: Already under PDPA Office review for balancing security with traveler consent (Bangkok Post, 28 Nov 2024).

- PDPA Enforcement: Fines up to THB 5 Million (+ criminal penalties) under Section 84 for violations.

Proactive Steps for Thai Businesses:

- Audit & Destroy: Review of all FRT deployments. Destroy non-compliant historical biometric data.

- Adopt Privacy-Enhancing Tech: Explore anonymized analytics or on-device processing.

- Update Policies: Explicitly detail FRT use in PDPA-mandated privacy notices (Section 23).

Conclusion: Prioritize Privacy or Face Penalties

The Bunnings ruling underscores a global reality: convenience and security claims cannot override fundamental privacy rights. Thailand’s PDPA enforces identical principles – requiring explicit consent, necessity, and radical transparency for FRT. Thai businesses risk significant fines and reputational damage (as seen in the 7-Eleven backlash) if they ignore these lessons. As PDPA enforcement matures, proactive compliance is no longer optional – it’s essential for maintaining ethical and legal operations in Thailand.

The information in this article is only for general knowledge and learning purposes. We’re doing our best to keep the information accurate and current, but there’s a chance that some details may be outdated or not entirely accurate. This article shouldn’t be treated as legal advice. For any questions, you may contact Formichella & Sritawat at info@fosrlaw.com

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC). (2024). Bunnings Breached Australians’ Privacy with Facial Recognition Tool [Media Release].

- Personal Data Protection Committee (PDPA), Thailand. (2019). Personal Data Protection Act B.E. 2562 (2019).

- PDPA Thailand. (2023). Guidance on Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA).

- Bangkok Post. (15 March 2023). "7-Eleven Faces Backlash Over Facial Recognition Trial."

- The Nation. (2 May 2024). "Major Bangkok Mall Halts Facial Recognition Pilot After PDPA Warning."

- Prachatai. (30 April 2024). "Privacy Concerns Mount Over Silent Rollout of Facial Recognition in Malls."

- Bangkok Post. (10 January 2024). "Airport Facial Scans Face Privacy Scrutiny."

- Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA), Thailand. (2024). Guidance Note: Biometric Data under the PDPA.

- Australian Privacy Principles. (2014). Schedule 1 of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).